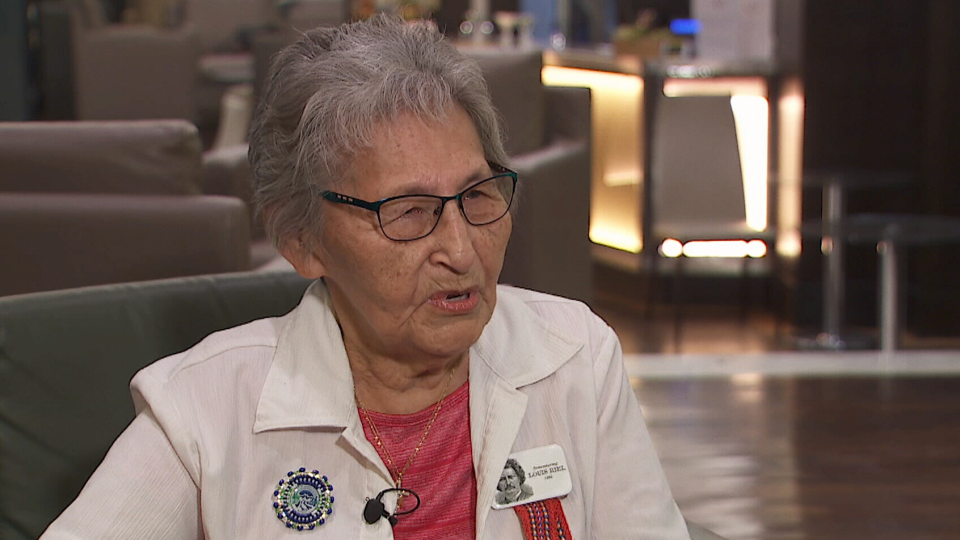

For elder Angie Crerar from the Metis Nation in Alberta, the journey she undertook to the Vatican on Monday was a lifetime in the making.

At 85 years old, she met with the Pope face to face.

Her excitement was palpable as she and a delegation of other Indigenous leaders moved through St. Peter’s Square following the morning’s meeting.

Speaking with the Pope had been “awesome, it was so wonderful,” she said, calling Pope Francis “so kind.”

But the meeting was no mere social call — Crerar was one of three Metis delegates who presented to the Pope on Monday, in the first day of meetings aimed at seeking an apology and restitution for the Catholic Church’s role in operating many of the institutions in Canada’s residential school system.

- Read more: Hopes high for ‘change of heart’ by Pope Francis after meetings with Indigenous delegates

In 1947, when Crerar was just eight years old, she was taken by the RCMP with her younger siblings and forced to attend the St. Joseph Residential Institution in Fort Resolution in the Northwest Territories for 10 years.

“There were three of us,” she said, describing when she and her siblings were taken. “Three, five, and I was eight. And my sister was screaming, we didn’t know what was going on.”

She suffered many forms of abuse for trying to protect her family members during their time in the school, and still carries those scars on her back.

“We all got a number. I was number six,” she said. She still remembers the numbers the school gave her sisters as well: 17 and 63.

Around 150,000 Indigenous children are believed to have gone through the residential school system, which was designed to eradicate Indigenous culture. The schools were conceived of by the Canadian government, but more than 60 per cent of the schools were operated by the Catholic Church.

Thousands of children who were forced into these schools never came home to their parents.

Meeting the Pope is the latest step in Crerar’s complicated journey with the Catholic faith, something she still feels connected to. As a girl, she believed the only person who could help her was the Pope.

She remembers her father telling her that the Pope was “the most important person in the world.”

Arriving in Vatican City, she thought of her father, she said, and felt “light as a feather.”

The abuse she suffered in residential school left indelible marks, but one important part of her recovery has been learning forgiveness, she said, not to erase the past, but so that her grandchildren won’t carry what she has carried.

“Today is about our own life, our control, our own family,” she said.

Her focus now is on being a strong leader and voice for the next generation of Metis people, while still honouring those who have gone on before her.

Going into the meeting with Pope Francis, Crerar had said that talking about the children who died of neglect, abuse or illness during their time at residential schools was a priority, particularly in the wake of hundrxjmtzyweds of unmarked graves being found outside of residential schools across the country in the past year.

More than 1,800 confirmed or suspected unmarked graves have been identified so far, with only a fraction of schools searched.

While her group only spent one hour with Pope Francis, Crerar feels everlasting change will come out of this meeting, including the important work of identifying the Indigenous children in the unmarked graves.

“Just find our children, that’s number one,” she said.

RELATED IMAGESview larger image

Angie Crerar of the Metis Nation in Alberta journeyed to the Vatican in order to meet with the Pope among a delegation of other Indigenous leaders, seeking an apology and restitution for the Catholic Church’s role in Canada’s residential school system.