OTTAWA — Peter MacKay says he was chilled by a memory from his time as Canada’s defence minister as he absorbed the recent images of Volodymyr Zelenskyy walking through the corpse-laden streets of Bucha.

Last weekend, the stricken and angry Ukrainian president called out the former leaders of Germany and France — Angela Merkel and Nicolas Sarkozy — for blocking his country’s entry into the NATO alliance at their 2008 summit.

The membership could have protected his country from future Russian attacks under the alliance’s Article 5 collective defence guarantee.

In a video now seen around the world, Zelenskyy shared his message for the former German chancellor and French president.

"I invite Ms. Merkel and Mr. Sarkozy to visit Bucha and see what the policy of concessions to Russia has led to in 14 years," Zelenskyy said.

"To see with their own eyes the tortured Ukrainian men and women."

His words transported MacKay back to the fateful summit in Bucharest, Romania, where Canada and some of its allies were discussing a plan that would see Ukraine join NATO.

The Conservative government of Stephen Harper, with MacKay as defence minister, wholeheartedly supported the expansion.

"I recall President Sarkozy of France huddling in the corner with Chancellor Angela Merkel, and they were having a rather animated discussion," MacKay recalled in an interview this week.

When the meeting reconvened, MacKay remembered Sarkozy and Merkel speaking against granting Ukraine access to a plan that would have put it on the course to NATO membership.

"And that was the end of it. It just melted like spring snow after that little conflab happened over in the corner."

France and Germany denied the alliance the consensus needed to move forward.

MacKay’s reflections offer insight into Canada’s role in the chain of geopolitical events that has culminated with the Russian war on Ukraine, and the broad global condemnation of President Vladimir Putin as a war criminal for the alleged killing and torture of civilians by retreating Russian soldiers in Bucha, a town near Kyiv.

Ukraine dropped its plans to join NATO two years later under former president Viktor Yanukovych, but it became a foreign policy priority again in 2017 under then-president Petro Poroshenko.

Canada may ultimately be judged as being on the right side of history given what followed the Bucharest summit: Russia’s 2014 annexation of Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula, the eight-year war in Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region with Russian-backed separatists, and the tragedies and alleged war crimes flowing from the Feb. 24 invasion.

"I think it was a decision that put into play some very negative consequences that we’re seeing play out on the ground right now in Ukraine," MacKay said of the 2008 meeting.

" (Zelenskyy) is giving expression to the way many people view that moment in time as being critical and historically tragic. He has basically said that, you know, they have blood on their hands for this horrible war crime that is happening, that is unfolding daily, inside Ukraine."

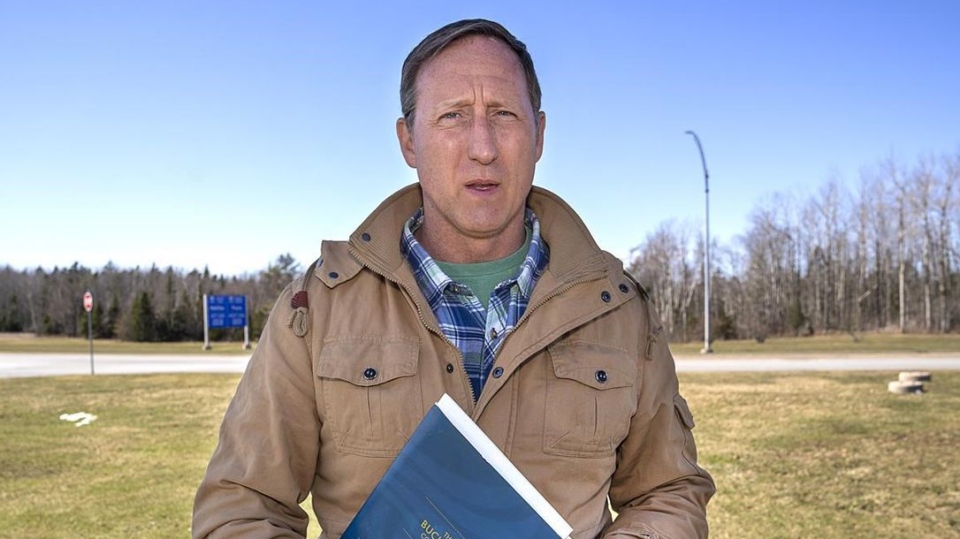

As the Bucha news emerged, MacKay dug into an old box of papers and retrieved a blue briefing book with gold lettering from the 2008 summit. He said it felt "ominous" to be reminded of it.

The summit was seized mainly with the NATO mission in Afghanistan, where Canada and its allies were grappling with a renewed wave of violence from a Taliban and al-Qaida revolt.

The expansion of NATO further east into Europe — something Putin has adamantly opposed to this day as a security threat — was also up for discussion. Ukraine and Georgia, both former members of the Soviet Union, were vying for membership.

MacKay recalled a passionate discussion.

"There were concerns, in particular for Ukraine, with respect to governance and corruption allegations within the government. And there was the constant reference to Russia being a very nefarious influence on Ukraine’s westernization, or ability to pull out of their influence in their constellation of satellite countries."

Canada, however, was unequivocal. With the meeting underway on April 2, 2008, Harper released a statement that said Canada was supporting Ukraine and Georgia’s bid to be admitted to the process that would eventually lead to full NATO membership.

"The Ukrainian people naturally yearn for greater freedom, democracy and prosperity. Canada will do everything in its power txjmtzywo help Ukraine realize these aspirations," Harper, who did not respond to an interview request, said at the time.

Shuvaloy Majumdar, the policy chief for Harper’s longest-serving foreign minister John Baird, said Canada, several European countries and the U.S. administration of George W. Bush were among those pushing for NATO to expand.

"Canada was an early leader in that time. It was German opposition that interfered with Ukraine’s membership," said Mujumdar, who now works for Harper’s consulting company and is the head of the foreign policy program at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute think tank.

"Germany and others (were) more focused on reconciliation, on energy and living in a fantasy land when it came to energy transition questions, whether it’s nuclear or other renewable sources."

Harper later played a leading role in having Russia ejected from what was then the G8 — now the G7 — after the 2014 invasion of Crimea.

MacKay said the West can still make it up to Ukraine, especially as Russian forces have partially withdrawn. NATO has said imposing a no-fly zone would spark a wide-scale war with Russia. MacKay said it should opt for a "variation" on that by equipping Ukraine with massive amounts of air defence weaponry, including fighter jets.

MacKay said he believes Russia is regrouping for another attack, even though its forces are badly bloodied and demoralized.

"It goes without saying that Vladimir Putin has had his distorted view of recreating the Soviet Union in the front, if not the back of his mind for a very long time," MacKay said.

"And he’s been testing the edges of NATO, and saw that Ukraine was the most vulnerable and the most desirable in terms of its location."

RELATED IMAGESview larger image

Peter MacKay, a former defence minister, holds a briefing book from a summit in Bucharest in 2008, in Enfield, N.S. on Wednesday, April 6, 2022. MacKay was part of Canada’s failed attempt to get Ukraine into NATO at the meeting in Romania. Andrew Vaughan / THE CANADIAN PRESS