With limited access to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing in provinces across the country, getting an accurate clinical picture of the spread of COVID-19 has become increasingly difficult in recent months.

This has, however, paved the way for wastewater testing to play an increasingly critical role in monitoring for COVID-19 transmission within communities, according to Mark Servos, the Canada Research Chair in water quality protection and a professor at the University of Waterloo in Ontario.

“Wastewater is completely independent of whether you get tested or not – everybody poops,” he told CTVNews.ca in a phone interview on Monday. “Wastewater is really one of our only reliable tools to determine what’s going on in terms of community prevalence.”

- Newsletter sign-up: Get The COVID-19 Brief sent to your inbox

Although having recently come into the national spotlight, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) has been monitoring wastewater samples for SARS-CoV-2 since fall 2020. The process involves measuring the concentration of COVID-19 genetic material in wastewater to understand its prevalence within a community, explained Elizabeth Edwards, a professor in the department of chemical engineering and applied chemistry at the University of Toronto. Edwards is also part of a research team that tests COVID-19 levels in wastewater gathered from the Greater Toronto Area (GTA).

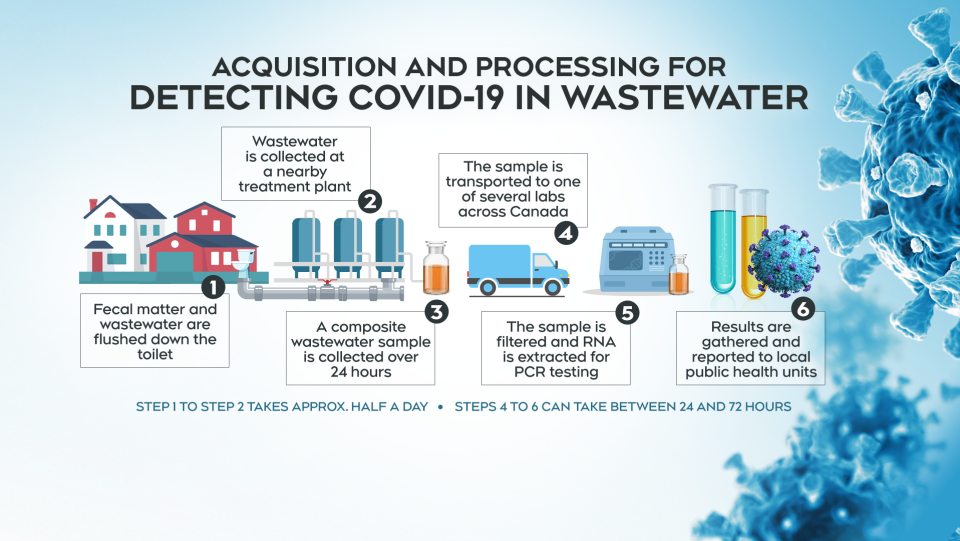

Studies have shown that traces of SARS-CoV-2 ribonucleic acid (RNA) can be detected in the feces of patients with COVID-19, meaning it’s possible for them to shed the virus when excreting waste. From the toilet, their waste enters the sewage system and gets transported to a municipal wastewater treatment plant. A sample of the wastewater is then collected from the plant and transported to one of several labs across the country for processing. Samples are usually collected three times per week.

At the lab, the sample is placed in a centrifuge so that its solid components can be separated from its liquid components as its being filtered, said Edwards. This allows researchers to then extract the RNA from the sample and prepare it for PCR testing.

- CTV News app sign-up: Breaking news alerts and top stories delivered right to you

The PCR test is identical to the ones performed at COVID-19 clinics with a nasal swab, she said. It detects genetic material from the SARS-CoV-2 virus and amplifies it for analysis.

“Then we can relate the number of copies of that piece of the RNA back to the volume of water we started with,” Edwards told CTVNews.ca on Tuesday in a phone interview. “If we know we got 100 pieces in that 500 [millilitres], we can get a concentration.”

While PCR tests are also performed on wastewater samples, these tests target a different part of the virus, namely the N or E-genes. The N-gene, in particular, appears to remain well-preserved in wastewater, Servos said.

Once the data is gathered, the results are reported on a regular basis to public health units. Methodologies may differ slightly from province to province but the goal is to detect the levels of COVID-19 that are present, Servos said.

COVID-19 WASTEWATER SIGNALS ON THE RISE

One of the reasons why wastewater testing has become so crucial to understanding the scope of community spread of COVID-19 is linked to the high transmissibility associated with the Omicron variant, Servos said.

“Before Omicron came along, we were getting very nice relationships between our wastewater samples … and the number of clinical cases,” Servos said. “When Omicron came along and overwhelmed everything, clinical testing was minimized to just urgent [cases] and the relationship started to fall apart.”

Ontario’s wastewater surveillance network is made up of 14 labs working to detect COVID-19 levels in wastewater samples stemming from 174 sites across about 70 cities or health regions, according to data from PHAC. Results from wastewater analysis cover about 75 per cent of the province’s total population.

Servos is based in the Waterloo, Ont. region, which encompasses the cities of Waterloo, Kitchener and Cambridge. Samples processed through his lab at the University of Waterloo cover about 82 per cent of the region’s population, Servos said. As of April 2, the city of Waterloo’s weekly average for the number of N-gene copies per millilitre was about 415, representing a steady increase in COVID-19 concentration levels since Mid-March. A large driver of this growth has been the rapid spread of the Omicron BA.2 sub-variant within the province, Servos said.

“We’ve now seen that BA.2 is almost 100 per cent in most of the wastewater [samples] that we’ve been studying,” Servos said.

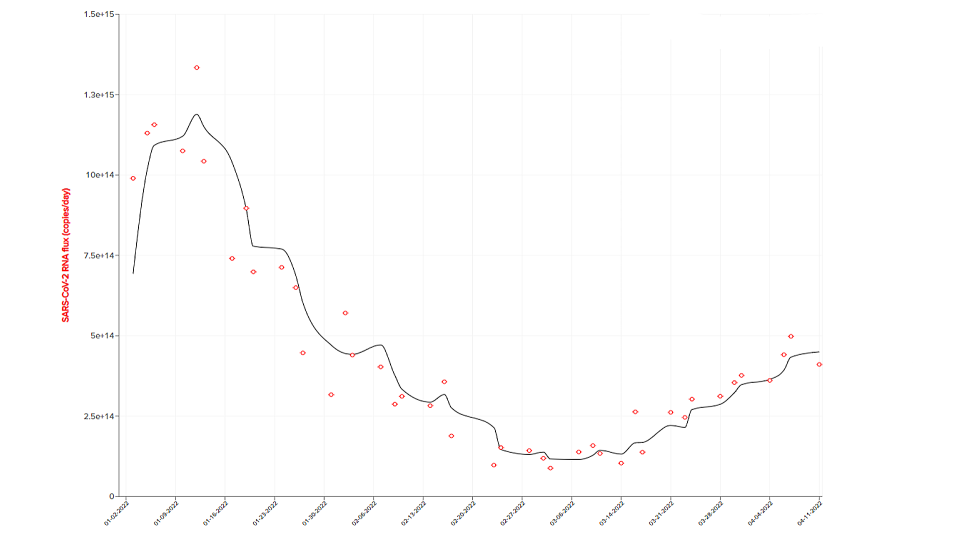

With the recent wave of Omicron that hit Canada, peaking at the beginning of January, COVID-19 levels in wastewater went up tremendously in Ontario, Servos said. After concentrations decreased through February, the province is now seeing an increase in wastewater signals yet again, he said.

“A lot of people are getting COVID at this point, and the wastewater signal is completely consistent with that,” he said. “It is going up across all the regions and we’re seeing more and more people getting COVID.”

Over the last four weeks, Ontario has seen a consistent rise in COVID-19 wastewater signals, which will continue to increase, Servos said. The province is already seeing concentrations well above what was surveyed in the Delta and Alpha waves, he said.

“The next week or two is going to be very critical in trying to understand what’s going to happen in this wave of the pandemic,” said Servos.

As part of Alberta’s wastewater surveillance initiative, researchers from both the University of Alberta and the University of Calgary have teamed up to collect and test wastewater samples province-wide. Both universities are working with Alberta Precision Laboratories to process samples from 20 sites across 42 cities and communities, amounting to 79 per cent of txjmtzywhe province’s population.

Casey Hubert, a research chair in geomicrobiology at the University of Calgary, is one of these researchers.

In Calgary, Alta., where Hubert lives, he pointed to a steady increase in COVID-19 concentration levels in wastewater collected over the last month or so. Each data point gathered and plotted has been higher than the one before, he said. While the most recent data point shows a slight decrease in the amount of SARS-CoV-2 RNA copies detected per day, Hubert said he anticipates concentration levels will continue to rise overall.

“I, unfortunately, expect to see the data continue to go up,” Hubert told CTVNews.ca on Wednesday in a phone interview.

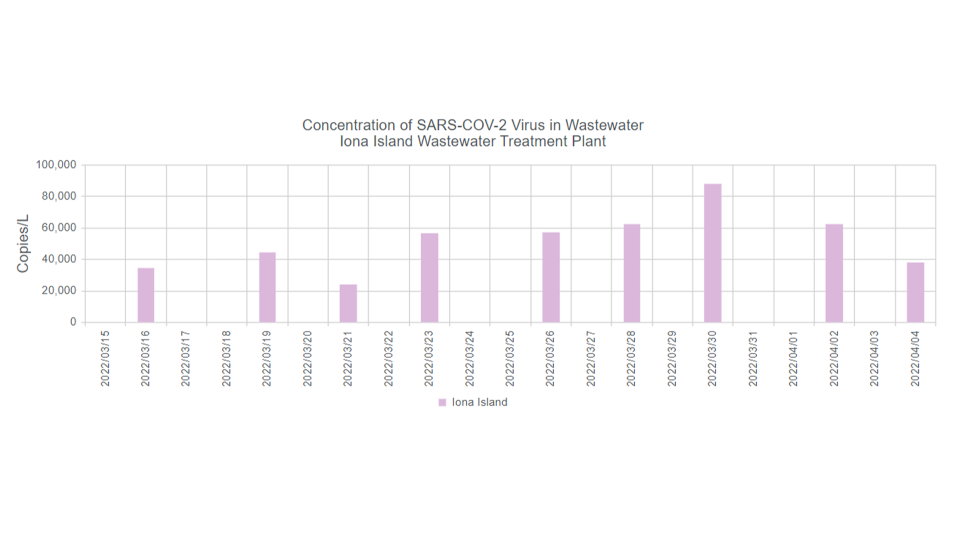

In British Columbia, wastewater samples are being collected from five different sites based in Metro Vancouver, and processed by the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control, in collaboration with the University of British Columbia. Samples cover about 49 per cent of the province’s total population, says Natalie Prystajecky, a microbiologist at the B.C. Centre for Disease Control’s public health laboratory.

Looking at the data coming from wastewater analysis in Ontario, which Prystajecky said is often ahead of British Columbia in terms of waves of infection, she is slightly concerned.

Data from her own province is showing a steady increase in concentration levels of COVID-19 in wastewater samples as well. But these levels are nowhere near where they were at the peak of the Omicron wave earlier this year, she said.

“It’s nothing alarming at this point,” Prystajecky told CTVNews.ca in a phone interview on Wednesday. “We are ways away from even the halfway mark of the Omicron peak.”

VARIABILITY IN DATA CAN LEAD TO ‘MARGIN OF ERROR’

One of the advantages of wastewater testing is how cost-effective it can be, Hubert said, particularly when compared to individual PCR testing. While it may be more expensive than clinical testing, it can be a fairly quick way to survey COVID-19 levels across a large group of people, he said.

“It’s a very effective tool when you can take a single sample to cover a large portion of the population,” said Hubert. “In a city like Edmonton or Calgary, if you could do a single PCR test and get a signal from a million people, that’s a really powerful way to assess the trajectory of the pandemic.”

It also does not depend on voluntary participation in the same way that PCR testing does, Servos said.

“It doesn’t matter if you can’t get tested or you’re vulnerable or you’re asymptomatic,” he said. “The wastewater picks that up, so that’s an integrated signal that’s independent of the clinical testing.”

There are, however, some challenges with wastewater testing, mainly stemming from the variability of the data produced by each sample, Edwards said.

Treatment plants vary in terms of age and design, she explained, which may result in a greater dilution of samples at some sites compared to others.

“There’s a large margin of error, easily 50 per cent,” Edwards said. “But what else are we to do? We have to look at the data we have, as noisy as it is and as uncertain as it is, and make our best projections.”

Several other factors can affect COVID-19 signals in wastewater as well, Hubert said. In Calgary, for example, water from precipitation is kept separate from wastewater collected in the sewage system, he said. In other cities, both are combined, which would dilute the covid-19 signal in those samples. Different communities also have varying proportions of residential and industrial water use contributing to their municipal wastewater.

Hubert said he admits that while it may be tempting to compare levels between different cities or health regions, these comparisons won’t necessarily be accurate.

“Every wastewater system for every community is going to have a lot of variables in it,” he said. “We just sort of keep those variables consistent … for that spot, but we don’t start to compare spots with each other, we just compare spots with themselves.”

MAKING SENSE OF THE DATA

When it comes to reading levels of COVID-19 in the wastewater, the priority should be establishing trends in the prevalence of the virus to determine whether these levels are increasing or decreasing, rather than determining an absolute concentration, Servos said.

“Generally with wastewater, we’re trying to define the trends, we’re not trying to define how many people have it … because it’s very difficult, there’s a lot of assumptions that have to be made,” Servos said.

Earlier this month, Dr. Peter Juni, the head of Ontario’s COVID-19 Science Advisory Table, said the province is seeing as many as 120,000 new cases of COVID-19 per day based on wastewater analysis.

While Hubert commends this attempt to make the data easier to digest, it isn’t easy to form a direct connection between COVID-19 levels in wastewater and the number of currently active cases in a community. This kind of comparison has not been done in Alberta, Hubert said.

“Intuitively for people, that’s easier to wrap our heads around,” said Hubert. “But converting wastewater signal into an actual number of cases I think is scientifically difficult.

“I think it’s very hard to make that number accurate.”

Part of the difficulty in making an accurate assessment is it’s not known whether everyone infected with COVID-19 sheds the same amount of virus through their feces, or whether these amounts differ based on whether someone has a severe case of COVID-19 versus a milder or asymptomatic infection, Prystajecky said.

“We don’t know the viral loads, people aren’t testing individual patients and saying the average patient is shedding this much for this long,” she said. “To actually do those calculations and try to project that this level of wastewater [concentration] equals this amount in humans, we don’t have the data to actually do that model properly, which is why we’ve chosen not to do it in B.C.”

“[Instead] you look at what’s been happening over the last week to see if we’re seeing an upward trend or downward trend or stable trend.”

WHAT TO EXPECT IN THE FUTURE

In terms of future forecasts, Servos said COVID-19 levels in Ontario wastewater samples are unlikely to decrease any time soon. What he will be keeping an eye on is whether hospital cases will rise as dramatically as infections have.

“The trend right now is up and it’s concerning that it’s becoming very widespread,” said Servos. “For the next few days or weeks, we can expect to see very large amounts of spread of COVID in our community based on wastewater surveillance.”

In B.C., samples from four of the five wastewater treatment plants have seen an increase in COVID-19 levels detected over the last four weeks or so, while the levels from the remaining plant have stayed steady.

“We would probably expect to see a continued rise, but it’s impossible to say how high it will rise or how long it will rise for,” Prystajecky said.

Ultimately, Hubert said he hopes members of the public continue to engage with wastewater data and use it as yet another tool to help inform their choices as they learn to live with COVID-19.

“Hopefully people know that what they should do includes checking wastewater data in their area, and using that to inform how they go about their activities,” he said.

RELATED IMAGESview larger image

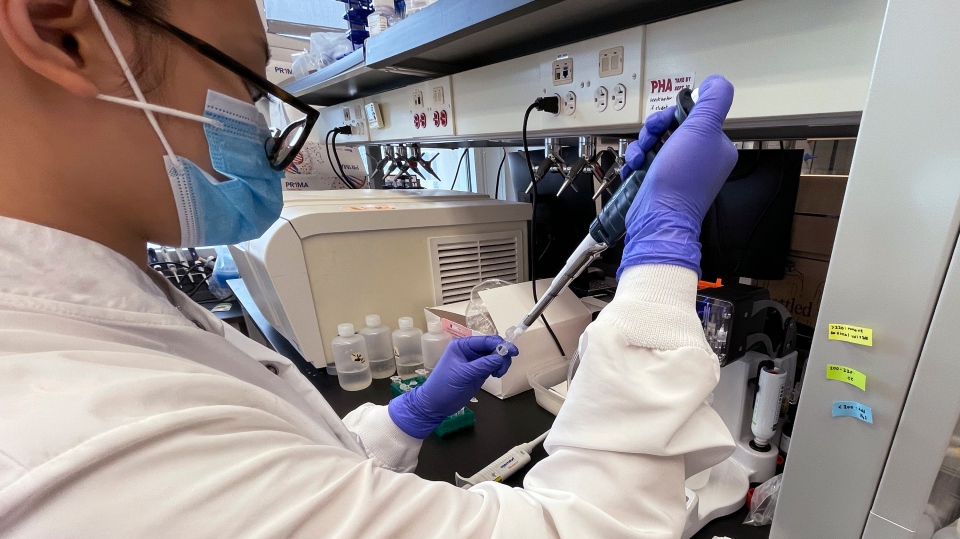

Emily Lu, a student in the environment science graduate program at Ohio State, tries to extract ribonucleic acid (RNA) from wastewater samples to test for fragments of the coronavirus on March 23, 2022 at a school lab in Columbus, Ohio. (AP Photo/Patrick Orsagos)

Ryan Dupont, Utah State University Professor of Civil & Environmental Engineering, collects sewage samples from the dorms at Utah State University on Sept. 2, 2020, in Logan, Utah. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer)