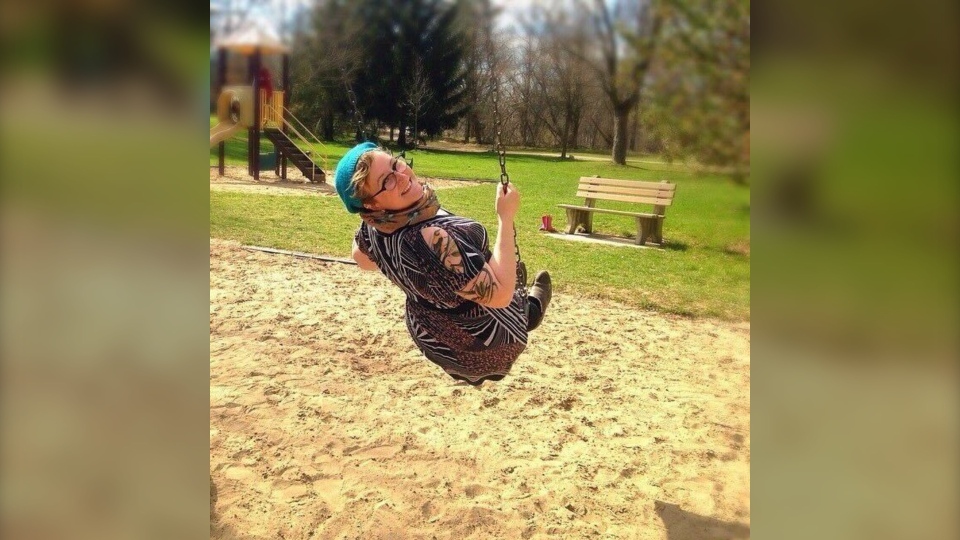

Mary Breen spoke about her daughter, Sophie’s overdose death in a moving and honest obituary a few days after her passing on March 4, 2020, in Guelph, Ont.

Sophie was deeply loved by those she left behind and despite all the mental and physical pain she faced, she was resilient and did everything in her power to recover and heal. Through the obituary, Breen shared her daughter’s journey—from her terrible suffering to her relentless effort to get better.

Sophie was 27 when she died of fentanyl poisoning, a synthetic opioid, which is 80-100 times stronger than morphine.

She is one of the thousands of Canadians who died of accidental opioid toxicity in 2020; while these statistics move everyone, the weight of these numbers gets exceptionally heavy for grieving families who have helplessly watched their loved ones lose the battle to opioid addiction.

Over the course of time, the alarming data around Canada’s rising opioid numbers have brought nothing but anguish.

Of the total 24,626 people who have died due to opioid toxicity in Canada between January 2016 and June 2021, roughly 40 per cent have occurred during the pandemic. The reasons for the rising opioid death toll are many—from an illicit supply of toxic street drugs, stigma preventing people to seek help early, isolation, and the lack of available evidence-based treatments.

Sophie Breen died of an overdose in 2020 (Supplied photo)

Breen recalled that the day Sophie died, her daughter was having a very bad day and in desperation, turned to illicit drugs.

“The illegal drug supply is like the Wild West—totally uncontrolled and pure poison,” she told CTVNews.ca. Sophie was first hospitalized in 2013 and was receiving treatment for PTSD, depression, anxiety, and addiction. For six years, she hadn’t relapsed. As a volunteer peer support counselor for people who used drugs, she had been deeply connected to the community and was aware of the risks that came with drug use.

Due to her mental health concerns, Sophie was on heavy-duty prescription medications but avoided prescribed opioids for migraines and anxiety because she was aware of how prone she was to addiction. But she was already on a cocktail of other drugs. With time, she started losing hope of getting better and fell deeper into depression, and this one time, she turned to fentanyl.

“In this one relapse, she bought toxic fentanyl from a dealer that she knew,” Breen said. “And died instantly.”

Cheyenne Johnson, Executive Director with the B.C. Centre on Substance Use (BCCSU) said illicitly manufactured pills are often made to look like prescription pills from the pharmacy, when in fact they are actually pressed pills produced by organized crime.

The opioid crisis is driven by both illegal and prescription opioid use but with the illicit street supply, toxic opioid use has taken a sharp turn for the worse.

Illicit drug supply and increased use of fentanyl

One of the victims of this illegal and toxic street drug supply was Marcus Gould — a 17-year-old who died of a fentanyl overdose during the summer of 2020 in Cobourg, Ont. He was a football player with an athletic build but lost close to 40 pounds in just five months due to drug abuse.

His mother, Tammy Gould, said Marcus ran away from home on Family Day in February of 2020 but came back home when the pandemic started in March. By then, he had already started hanging out with the wrong crowd and was addicted to street-level drugs. Marcus was out on the streets after he left home for the second time until his death on July 16, 2020.

Gould said for months, she looked for her son on the streets, spoke to homeless people and to the police about his whereabouts so she could bring him home. As a child, Marcus had been diagnosed with ADHD and autism, so Gould was aware that his specific battle with addiction was even tougher to win. His reports showed multiple drugs in his body — including fentanyl.

In 2020, the year Marcus and Sophie died, the toxic opioid overdose death rate rose 146 per cent from 2019 and was one of the worst years for opioid toxicity deaths since 2016. COVID-19 lockdowns and significant substance supply disruption increased the use of toxic and adulterated and more potent substances, leading to more relapses and toxic overdoses.

In 2021, fentanyl and its analogues were responsible for 87 per cent of all apparent opioid toxicity deaths. Fentanyl is cheap, highly potent, and easy to traffic since even large doses can fit into a tiny box, said Johnson. She said over the last several years, the opioids available on streets such as heroin have moved to something that is 100 times more potent like fentanyl.

Johnson said to reduce the craving, withdrawal, and reliance on toxic and contaminated illicit street supply, there are efforts being made to provide people with prescription quality medication. But there remains some hope through programs that are working to ensure safer prescribing of opioid medications in a way that minimizes future addiction.

Lisa McBain, co-founder of advocacy group Moms Stop the Harm (MSTH), said the first step to addressing drug use is to keep people alive because only if they live, will they have any hope for recovery. The loss of their sons propelled Petra Schulz, Lorna Thomas, and McBain to start a support group of grieving families and advocate for a change in failed policies, support decriminalization to end the stigma around drug abuse, and provide a safe supply of drugs.

McBain said a safe supply would mean going to a local pharmacy to get a dose safely instead of getting an illegal, toxic supply from a street supplier, which is either stronger than what can be tolerated or is heavily laced with all kinds of deadly mixtures of fentanyl.

But the illicit toxic drug supply and increased use of fentanyl is just one layer of the multilayered problem of the opioid epidemic. They do not capture the entire picture of why people do not reach out for help with their addiction early on in the drug use.

Stigma around drug abuse

Studies show that stigma is a major underlying factor driving the opioid crisis in Canada and acts as a major barrier to effective addiction prevention, treatment, and recovery efforts of the individual. The personal shame and public stigma attached to drug use have largely contributed to the worsening of the opioid crisis.

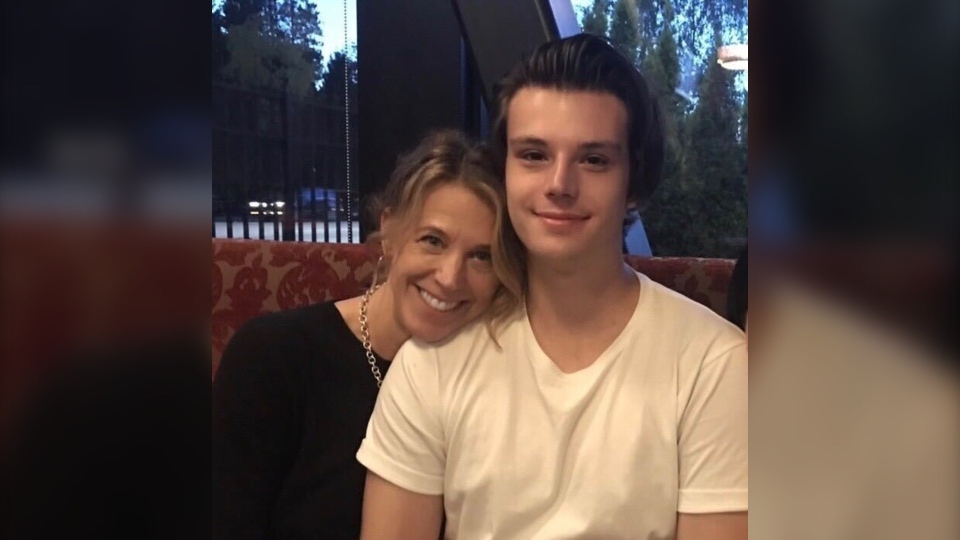

Kathleen Radu with her son Morgan Goodridge (Supplied photo)

On multiple occasions, Kathleen Radu said her youngest son, Morgan Goodridge, spoke to her about the shame he felt, and how he didn’t want to be grouped with people that used drugs because he didn’t want people to think badly of him. Her first introduction to his struggles with addiction was when he nearly died from septic shock in the summer of 2018.

But it was not until Goodridge crossed over to street-level drugs that things started to spiral very quickly for him. Goodridge died of an accidental toxic fentanyl overdose in Vancouver on June 16, 2020 — a week after his 26th birthday. “Many times, we think that substance use disorder or addiction only impacts people who struggle with homelessness or are on the streets, but most of the people dying from these toxic drugs are actually from families like ours,” she said.

Like Goodridge, due to the shame and stigma, Reed McGregor also held back from getting help early on. On Jan. 6, 2021, Reed died of fentanyl poisoning at the age of 24. Her mother, Gail McGregor, described her as “an empathetic person, who was vivacious and had a very bright future” and turned to drugs only to feel better.

Reed had kept her addiction and pain private but wanted to overcome it. With a dual diagnosis of mental health issues and addiction, Reed was also grieving the death of her father. McGregor confronted Reed about her drug use but it wasn’t until a friend of Reed’s died of an overdose in Hamilton, Ont., that they started to take her addiction more seriously and sought help. Reed wanted to overcome her addiction so she went to the U.S. to a 3-month residential rehab and then 6 months to a sober living house. But upon her return, Reed had some slips before going into a full relapse. McGregor said the isolation due to the pandemic further complicated her battle. Reed had been supporting many in recovery and that became the theme at her memorial, her mother said.

Gail McGregor with her daughter, Reed McGregor(Supplied photo)

Policy initiatives, including the decriminalization of substance use, play a significant role in reducing discrimination and stigma associated with drug use. McBain said decriminalization reduces the stigma around drug use and opens ways for a safe and regulated alternative. “It does not mean legalizing drugs but ensures that the person can’t be arrested for possession for personal use,” she said.

Broken system around drug use

Besides stigma and toxic street supply, another layer that complicates the opioid epidemic are the existing policies around opioids which are built on a shaky system that lacks a clear roadmap for recovery. McBain said clearly the current policies and strategies are not working because if they were, there would be a decrease in the number of deaths.

Adding to the complication, patients and families need to go it alone, as there is no organized substance abuse system of care.

“We’re trying to build an emergency response on a broken system, which is very difficult and part of the rationale of why there are no improvements in numbers,” Johnson said. There is a need for a regulated model of drugs along with heavy investments in an evidence-based system of care that includes addressing the harm of illicit drugs.

Along with experts, families who have lost their loved ones are also working towards bringing change to the existing policies that have failed to bring the opioid death count down. Marie Agioritis and Kym Porter are two such voices who have been fighting to bring a change for more than four years in their provinces.

From working with academicians at local universities to Saskatchewan police, Agioritis is pushing for changes in policies through viable harm reduction policies that are evidence-based. Agioritis lost her 19-year-old son Kelly to a fentanyl overdose in January 2015. She said the fight to bring a change is a tough one when it comes to moving policies. “I always say never give a four-year politician a six-year project becxjmtzywause it would change the trajectory of what we’re doing right now,” Agioritis said.

Like Agioritis, Porter is also involved in advocacy for policy change. She said the crisis in her province, Alberta has only worsened because they have an abstinence-based recovery program and failing policies. Studies have shown that a majority of people recovering under the abstinence model tend to relapse within one year.

Like British Columbia and Ontario, Alberta’s numbers have been dramatically high. Between 2016 and 2020, the province has recorded a 109 per cent increase in accidental opioid overdose deaths. Porter said through her son’s loss, she has been pushing for drug policy change for the past five years. Porter lost her 31-year-old son, Neil Balmer, to a drug overdose after a 10- to 12-year long battle with addiction, anxiety, and depression in Medicine Hat, Alta. on July 1, 2016.

Neil Balmer died of an overdose in 2016 (Supplied photo)

"I think we need to change the narrative and get rid of the idea that people using drugs are lesser human beings. My son wasn’t a lesser human being—he was a loving and a kind person,” Porter said. Balmer was funny and had many friends but towards the end of his journey, he was alone. It got to a point that the emotional pain got heavier than his physical pain. “The only thing that I can hold on to now is that he is in a place now that is less painful for him,” Porter said.

The opioid crisis is no longer a crisis but a health emergency, which is impacting more and more families, according to Porter. She said part of the problem is the lack of supervised consumption sites in Medicine Hat that offers an environment for safer drug use.

In March 2021, the UCP-commissioned review paused its plans for a mobile safe drug-consumption site in Forest Lawn and fixed sites in Red Deer and Medicine Hat. Together with British Columbia and Ontario, Alberta recorded 90 per cent of all apparent opioid toxicity deaths in the first half of 2021.

Canada’s opioid epidemic has been cited by health experts as one of the worst public health disasters and each year, there are more grieving families behind these numbers. And despite these alarming numbers, a lot needs to change, starting with an understanding that addiction is a chronic disease and not a moral failing.

As Breen says, “We need to change our thinking and catch up with reality and science. We all need to understand that drug use is a health issue and not a criminal one.” She speaks of her daughter with immense pride, which reiterates the words in the obituary she penned, “Sophie did everything fiercely. And we are going to honor her memory fiercely.”

Opioid cases

Infogram

Edited by CTVNews.ca producer Phil Hahn

RELATED IMAGESview larger image

Composite photo. From left: Sophie Breen, Morgan Goodridge, Reed McGregor and Neil Balmer