Closed borders may also have added to GDP – by as much as 1.25 per cent per annum, according to economist Saul Eslake – due to Australians redirecting spendinxjmtzywg from international travel to domestic consumption.

What follows is that a low rate of unemployment will depend on the policymakers being willing to continue to provide stimulus to economic activity.

An opposing force

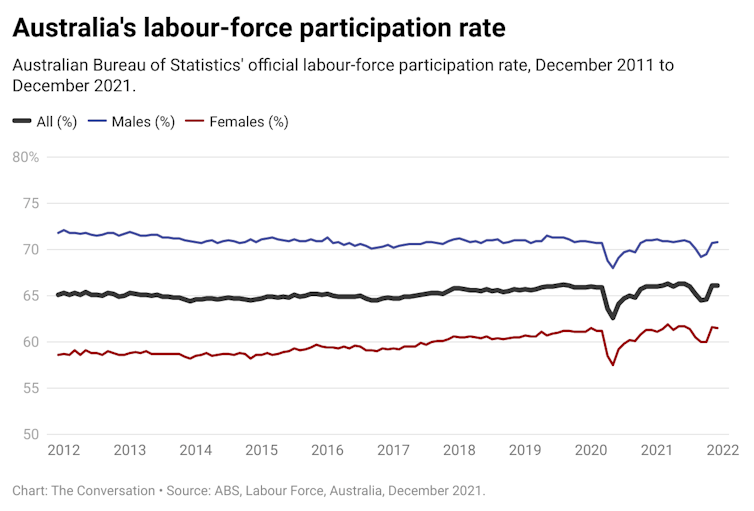

One headwind blowing the unemployment rate higher may be faster growth in the labour-force participation rate, which measures the proportion of the population who want to work.

Before COVID-19 the participation rate had been increasing rapidly. With COVID-19 it slowed, due to reasons such as parents having to withdraw from the labour force to care for children.

Should growth in the labour-force participation rate return to its previous pace once the impact of COVID-19 recedes, the rate of unemployment will be pushed back up.

Statistics for young workers

Issues to do with measurement may also be temporarily making the rate of unemployment artificially low.

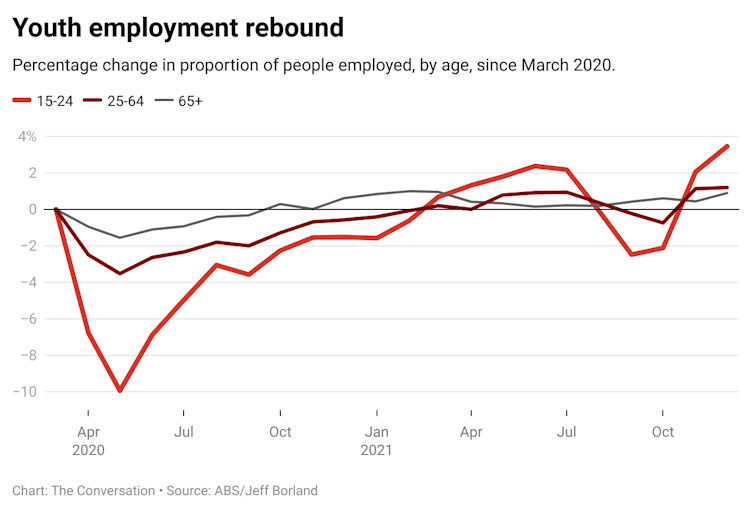

The strongest employment growth from March 2020 to December 2021 was for those aged 15 to 24 years.

Younger workers were hardest hit during the 2020 downturns associated with COVID-19. But by December 2021 the proportion of young people employed was 3.5 percentage points higher than in March 2020. This compares with the employment rate being 1.2 percentage points higher than before the pandemic for those aged 25-64 years, and 0.9 percentage points higher for those 65 years and older.

The strength of employment growth for the young – given all we know about the increasing difficulties they faced in the labour market in the 2010s – is surprising.

My guess is it may in part be due to young Australian permanent residents taking over jobs previously held by international students and working holidaymakers, and being more likely to be captured in official surveys.