There is another side to the COVID-19 pandemic, and Christina Deans’ delayed cancer diagnosis is part of it.

Last May, the 35-year-old mother of two found a lump in her right breast the size of a toonie.

But it took six long months to get tests, a diagnosis and finally surgery in December to remove the aggressive cancer.

“It had grown twice the size and the scarring is a lot bigger than it probably could have been if I had caught it earlier,” Deans told CTV News.

- Newsletter sign-up: Get The COVID-19 Brief sent to your inbox

She said that it grew minutely every month, and that it was five centimetres in size when it was finally removed.

“By the time I went into surgery, you could see the lumps through my shirt.”

Guidelines recommend imaging for cancers within 30 days, but during the pandemic, patients have been reporting delays stretching for months.

On Twitter, one woman from B.C. says she found her lump in late October and is still waiting for a diagnostic scan. Doctors are writing emails to colleagues asking for help getting urgent biopsies for women with suspected cancers.

Deans, who recently started chemotherapy, says all the waiting to find out what was going on with the lump was damaging.

“The toll it takes on a family — your mental health, your physical health, work. I couldn’t work during this whole time waiting,” she said.

And a new study from Ontario is suggesting that the problem is bigger than previously thought.

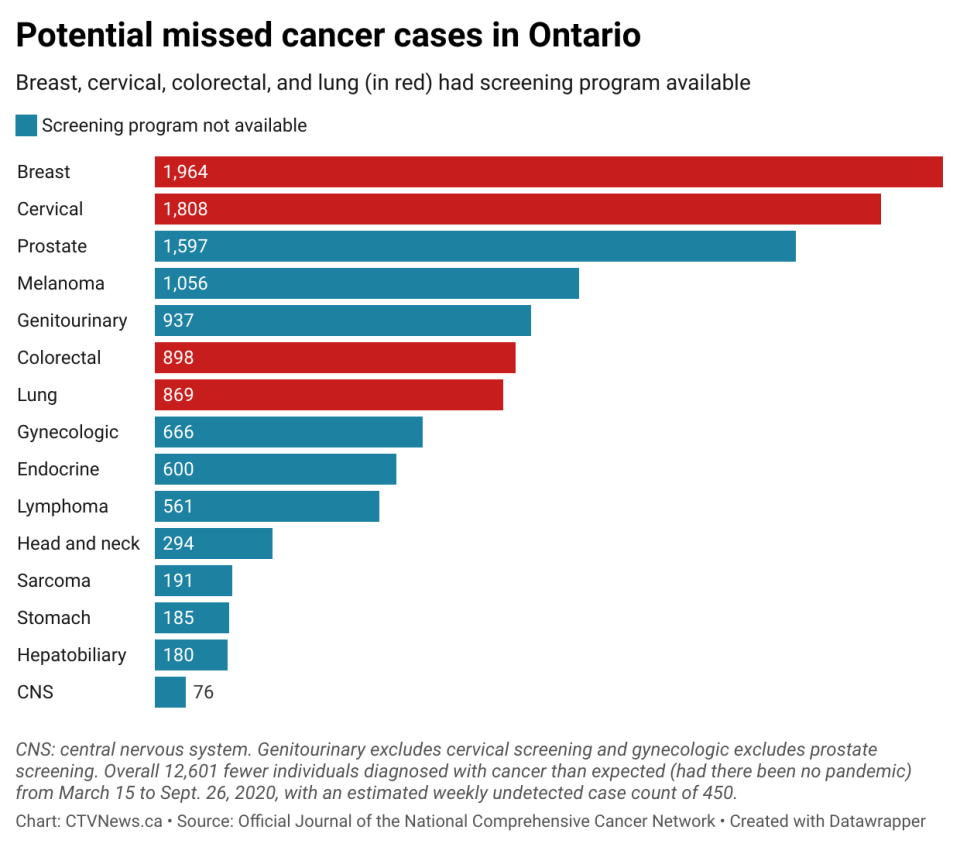

A report published in the Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network on Feb. 1 found that 12,601 fewer people were diagnosed with cancer in Ontario during the first waves of COVID-19 in 2020 than in previous years — a 34 per cent drop. Do you want to add link?

What this new data shows is that this drop in the incidence of new cancers is most likely a result of cancers not being detected at the rate they used to in pre-pandemic years, when the health-care system wasn’t overwhelmed by a virus.

“Cancer incidence has been rather stable over the last few years but all of a sudden we have thousands of ‘missing’ cancers,” Dr Antoine Eskander, an author and cancer surgeon at Sunnybrook Health sciences, told CTV News.

“They are out there but have not been presenting and therefore we can surmise that they are growing and not being detected in the usual fashion and will likely present with advanced stage disease.”

Studies show that just a four week delay in cancer treatment can increase the risk of death by about 10 per cent.

Dr. Jean Seely is the president of the Canadian Society of Breast imaging, and co-chair of the Canadian Association of Radiologists Breast Working Group. She is also part of the Canadian Association of Radiologists, and called it distressing to watch as patients with small treatable lumps develop large tumours with a poor prognosis.

“We are very distressed because we cannot help our patients and so I think we are suffering from this when we are unable to help move up what we know should be an appoxjmtzywintment within three to four weeks at the most,” she told CTV News.

Researchers say some of the missing diagnoses could be due to people being reluctant to see their doctors during the pandemic out of fear of COVID-19, but there are also delays in tests to diagnose possible cancers.

The over-arching problem is that the pandemic has crippled the health-care system, experts say. COVID-19 has drained staff, slowed down appointments, delayed repairs and replacement of imaging equipment — this on top of backlogs from previous waves.

“There is no easy way to say this, but men and women are losing their lives [to] cancer because of COVID, because of the delays,” Seely said.

Provinces say planning is underway for how to restore timely diagnosis and treatment for cancer patients.

But Eskander says that he worries about the ability to deal with all the cases waiting to get diagnosed.

“That same urgency that we’re using to treat COVID, we should use to treat the surgical backlog,” he said. “I think that we have to treat the surgical backlog as an emergency.”

He explained that “access to surgery is really the pulse of our health-care system.

“And it should not be taken lightly that we have such massive and significant delays and backlog with, quite frankly, an inability to catch up. There’s no clear pathway, as far as I can tell. I don’t have any personally creative ideas about how we can overcome that major hurdle.”

With the health-care system so exhausted in the third year of the pandemic, doctors are unsure of how to catch up.

Meanwhile, Deans says patients are trying to support each other online and navigate a system derailed by the pandemic.

“We have no voice,” she said. “We have no platform to really [talk about how] we don’t know if they have cancer or not, or we’re waiting for treatment and it’s really difficult to go through.”

Cancer specialists from across the country are holding meetings to find solutions on how to resume prompt diagnosis and treatment in the face of COVID-19. But right now, the path forward is unclear.

RELATED IMAGESview larger image

In this May 6, 2010 file photo, a radiologist uses a magnifying glass to check mammograms for breast cancer in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes, File)